There’s a common debate on Reddit, Instagram, whatever, about whether buying a property or renting one is better. The arguments are inevitably emotional and everyone gets very upset if their view isn’t the right one. Cries of: oh but I’ll own the property after 25 years or I get 15% returns on the stock market so it’s better clamour all around. There’s argument about whether a house is an asset or not, whether or not you can really get the purported 10% annualised returns from the S&P 5001, and what you’re going to do if you’re still renting come retirement.

The challenge issued from both sides is always: have you actually run the numbers?

So, I thought, why not? Let’s run the numbers and see what happens.

Some Caveats

I’ve made a lot of assumptions in this approach, which might not be accurate for your situation. The goal is to show how one might run the numbers, not come up with a definitive answer.

Another note: this analysis is going to get progressively more complex. We’ll start with fixed values and move on to some fancy Monte Carlo simulations (more on what these even are later). In fact I got so overexcited that after writing over 3000 words I decided this needed to be split into two articles. Hell, I might even do three.

Is it worth it?

The classic thing we’re told in most of the developed world is that you should do everything you can to save money and get on the property ladder. Once you’re on it, Elysian Fields await. Your capital grows an a rate that far outweighs the cost of your labour and in 25-30 years (once you’ve paid off your mortgage you’ll be a millionaire).

We’re going to test both of these hypotheses.

Firstly, is it better to rent or buy in the shorter term? Secondly, at what point does owning a house become profitable and make you a millionaire.

To work out if a property is worth buying or not, we need to think about some numbers. This table shows the inputs I’m going to be using for the model (I’ll explain each one).

Let’s break them down.

Property cost and deposit are hopefully obvious. Annual interest rate is what you’re going to pay on your mortgage. Have a look at money supermarket or whatever price comparison site you like to check rates.

Years Owned is how long you’re planning on keeping the property for.

We’ve got Appreciation Rate, i.e how much we think the property will go up by year on year (4% in this case).

Rent (Monthly) - how much rent we’re going to pay and how much that will increase year on year. Perhaps 2% is too generous to those evil landlords but that’s what I’ve chosen so deal with it.

The Cash Investment Return rate is how much we expect to get on our cash investment in the stock market. Maybe this is too high, but maybe a 4% appreciation yearly in the property is also too high so let’s leave it as it.

Inflation Rate is obvious, assuming you’ve read the news in the past two years.

Reinvest Rent Savings - whether or not we reinvest the rent saving (if any). So let’s say you get a mortgage that’s 3400 a month and your rent would be 3000, then you’re going to save 400. Do you reinvest this saving or not? I like to think of myself as very clever so I’m going to reinvest that saving.

Save Purchase Costs - the amount we spend in stamp duty and legal fees could have been put in the stock market too, and this is whether or not we’re savvy enough to do that.

Interest Only - is the mortgage interest only? I actually added this and then kept it false for all of the calculations because not everyone is eligible for one of these so it seemed a bit redundant.

Calculations

Okay so now we need to work out some things. We need to work out how much money we’re going to have at the end of the 5 years if we were renting or if we were buying. I should note that I’m just going to run through a lot of calculations here to you can see what each one does and means in the 5 year period.

Renting

I’m going to start with renting because the maths is easier.

The total cost of renting over 5 years is represented by this formula:

So put the numbers in:

This accounts for our 2% rent increases a year across the 5-year period.

So so far for renting we’re down -185,400. Not bad.

Not let’s say instead of putting down the deposit, we invested it in the S&P 500 (which has returned 15% in the last 5 years by the way) and say we get 4% a year compounded - because we’re really bad an passive investing.

Represented by these formulas:

The principal in this case is our 100k deposit.

Our measly, passive-investment driven, return then is: 110,196.00. However we are reinvesting our saving of 668.43 a month so in reality after 5 years we have 173,374.77 (gotta love compound growth).

So to work out out total outgoings in rent we do:

So we’re still dramatically down -13,970.7 but the question is can we do any better if we buy the property?

(Note: that this is without reinvesting the difference in mortgage vs rent - I’ll get to that later).

Buying

Buying is a little more complex since we need to account for stamp duty, legal fees, maintenance for the building etc. We also need to work out what we’re going to repay over the 5 years.

Mortgage Repayment

You can’t get a 5 year mortgage so instead we’ll get a 30 year one, since 30 year mortgages are becoming increasingly popular.

We can work out the total cost of the mortgage with this formula:

Which gives us a monthly payment of:

So the total we’ll pay against our mortgage monthly is £3668.43 and the total cost of our mortgage over its 30 year lifetime is approximately £ 1,335,898.80.

And we’ll have a remaining mortgage balance of £ 627,242.16 when we come to sell the property in 5 years, and we’ll have paid £220,105.65 to live in the house.

Additional Fees

Now let’s work out stamp duty, legal fees, and our very generous 2000 a year in maintenance, which of course assumes that the roof doesn’t fall off week one, or you set the house fire, or a high-pitched soprano knocks out all the windows.

Let’s start with legal fees because it’s easy. The cheapest quote I could find was 2700 including VAT. We’re not buying this as a business to we’re paying VAT. The reason the legal fees are 3200 not 2700 is because of the loan fee. With the quote of 4.74% there was a loan fee of 500. I’m just adding that to the legal fees for simplicity.

Next up maintenance. It’s not atypical to say the annual maintenance is 1-2% of the property value a year2, which would be 8000 a year.

But I’m going way below that at 1000 because I really want to make this profitable. Across the 5 years that’s 5000.

Stamp duty is where the controversy comes in. I’m going to assume this is a first home purchase and use the online stamp duty calculator. I’ve built this into the program but for now just trust me that the stamp duty due is 27,500.

So our total cost of purchase, just the additional fees we need to pay, is:

Property Value Appreciation

Lastly let’s work out how much our house will have gone up in value. It’s the same as the ROI formula above. You can put the numbers in but it’s 804, 676.07. Although let’s be clear that a property in no way benefits from compound interest, despite what some buy-to-let gurus will tell you. It does get compound growth though so I’ll leave it as is.

Net Buying Position

Okay that’s a lot of numbers but we can finally work out our net buying position.

To buy the house we spent a total of: 110,700. This is the deposit plus our legal fees and stamp duty, and assumes we didn’t have to pay any fees to take out the loan.

And we paid a total of: 225, 091.33 against the mortgage, and, in doing so, we paid off 72,757.84 of the principal.

When we come to sell, the house value is: 860,275 and assume a seller’s fee of 2% (23,646.60), so we’ll make back: 836,628 from the sale of the house.

This puts our net position at: -5,844. So we’re better off but really not by much.

This table contains all of the calculations from the house buying/renting option:

And as you can see the better option in this scenario is buying, but only after year 4, and we’re still 5k down. So basically you need to commit to living in a place for a minimum of four years for buying to become worthwhile, and this was of course with a much lower maintenance value than maybe be feasible.

When is it better to buy?

So our current calculations work across a 5 year timeline but what I really want to know as a perspective homeowner is at what point does my decision to purchase a property pay off? As in at what point am I no longer in the red?

It’s trivial for the program to work this out. All it needs to do is do the calculations on a yearly basis and then work out at what year buying becomes a better option.

Now across a 5 year horizon it’s never going to be profitable, but what if we bought the house with the assumption that we’re going to keep it for the full mortgage term, so in this case 30 years.

I run my little program and here’s the output for 30 years.

As you can see it doesn’t actually become profitable until year 17, and by year 30 we’re cruising.

Am I being too pessimistic?

Probably. 17 years to turn a profit on a house seems kind of insane, given the dream we’re all sold about owning a property.

So let’s have a look.

House prices in 2000 were £177,650.80 adjusted for inflation. Today they’re £265,240.00 (again adjusted for inflation), which is a 60% increase. But that’s 25 years ago. Over the past five years, they’ve gone down by about 5%.

What we really need is to be able to add some variation to our model. Rents could go up or down, the same for interest rates, and the value of our property or investment could too.

We can simulate this with a Monte Carlo simulation.3 Basically we can draw samples over a variable given our expectations about the future and use these samples in our program.

Below shows a distribution of possible interest rates. Note how it shows a range of possible values between -10% and 20%. This allows us to simulate interest rates for our model. So while we think they might stay at around 4%, what happens if they go up to 20% (unlikely but you never know). Drawing samples from this distribution allows us to see what would happen in that scenario.

Why is this useful? Well, introducing a level of random sampling means that we can account for possible fluctuations in interest rates in our calculations.

Now if you look at the chart we’re going to get more sample between 0% and 10% and very few either side. Perhaps we want to see more samples in the lower end because we assume that interest rates are going to go down in the next few years, then we can use a skewed distribution which would look as follows.

And this would give us more samples towards the 2.5% mark, which may be what we want since we’re optimistic about future interest rate cuts. Of course, you might be inclined to think that interest rates are actually going to go up, in which case we’d need to skew it the other way.

So we can tinker with the values in a reasonable way now, but what values should we actually allow to be change in this model?

Well, realistically there are four that are going to be most subject to fluctuations:

Interest Rates

House Value Appreciation Rates

Return on Investment Rates

Rent Increases

Inflation

You’re going to be able to change the deposit over the five year period because you’ve already spent the money (either by investing it or buying the house). The same applies to the cost of the property, legal fees, etc. Possibly the maintenance could go up or down. Around 82% of mortgages4 are fixed rate so let’s assume that we’re one of them, and assume that our interest rate cannot change in the five year period (perhaps I should’ve chosen a different variable to illustrate the Monte Carlo sampling).

So now let’s sample from our (adjustable) inputs:

House Value Appreciation Rates

Return on Investment Rates

Rent Increases

Inflation

Maintenance

I’m not going to skew them in any direction for the first run, because we’re going to get fancy later and work out what the skew should be for each metric.

Here are our initial distributions.

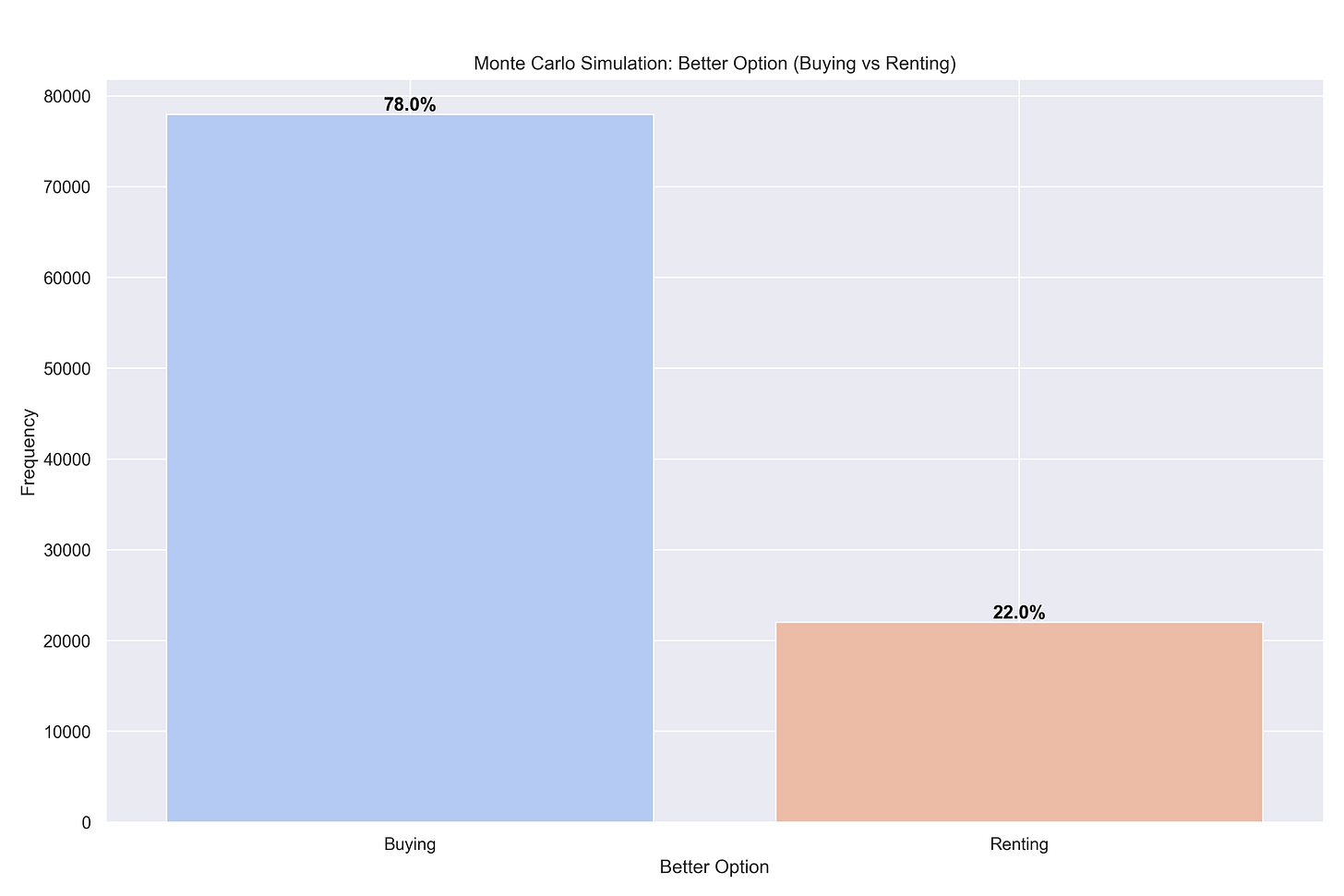

Since I’ve got a powerful computer I’m going to run it 100,000 times, and we’ll see how many times buying was better than renting.

As you can see buying is better 78% of the time. I, for one, am not surprised by this. The main factor that’s going to affect this is the interest rate and unless the property values appreciates at a higher rates, it’s never going to win.

Just for balance, let’s do this on a tracker mortgage too.

Slightly better odds for renting, but, it’s pretty obvious at this point that the odds are mostly in our favour with buying, although we are still in a net negative position.

Best and Worst Case

While this is useful, what I really want to know is under what circumstances buying is consistently better and under what circumstances renting is consistently better. This is easy to work out, we can just take a mean of all the variable inputs for each case.

Here they are without the varying interest rate

The table below shows under what average conditions buying is better. It’s interesting that we need quite consistently high rent increases for it for be viable. But this is a mean so it means we might have sampled a very high rent increase, say 15% that skewed our average.

For renting to be better, we need negative property price appreciation rates, which given the past five years is entirely possible.

What I find interesting here is that we don’t necessarily need super low rent increases, we just need a better investment return rate. Although the interest rates rises are not very likely in the five year term.

How to make an informed decision?

I haven’t really looked at a realistic outlook for interest rates, or property appreciation rates over the next 5 years. While the Monte Carlo simulation is useful, its random nature means that it’s going to try out a whole range for scenarios, rather than more realistic ones.

What we need to do is look at historical house prices and also historical interest rates and then try and predict what’s going to happen to house prices in the next 5 years.

Here’s a chart of historical house prices since the year 2000, with real being the prices adjusted for inflation.

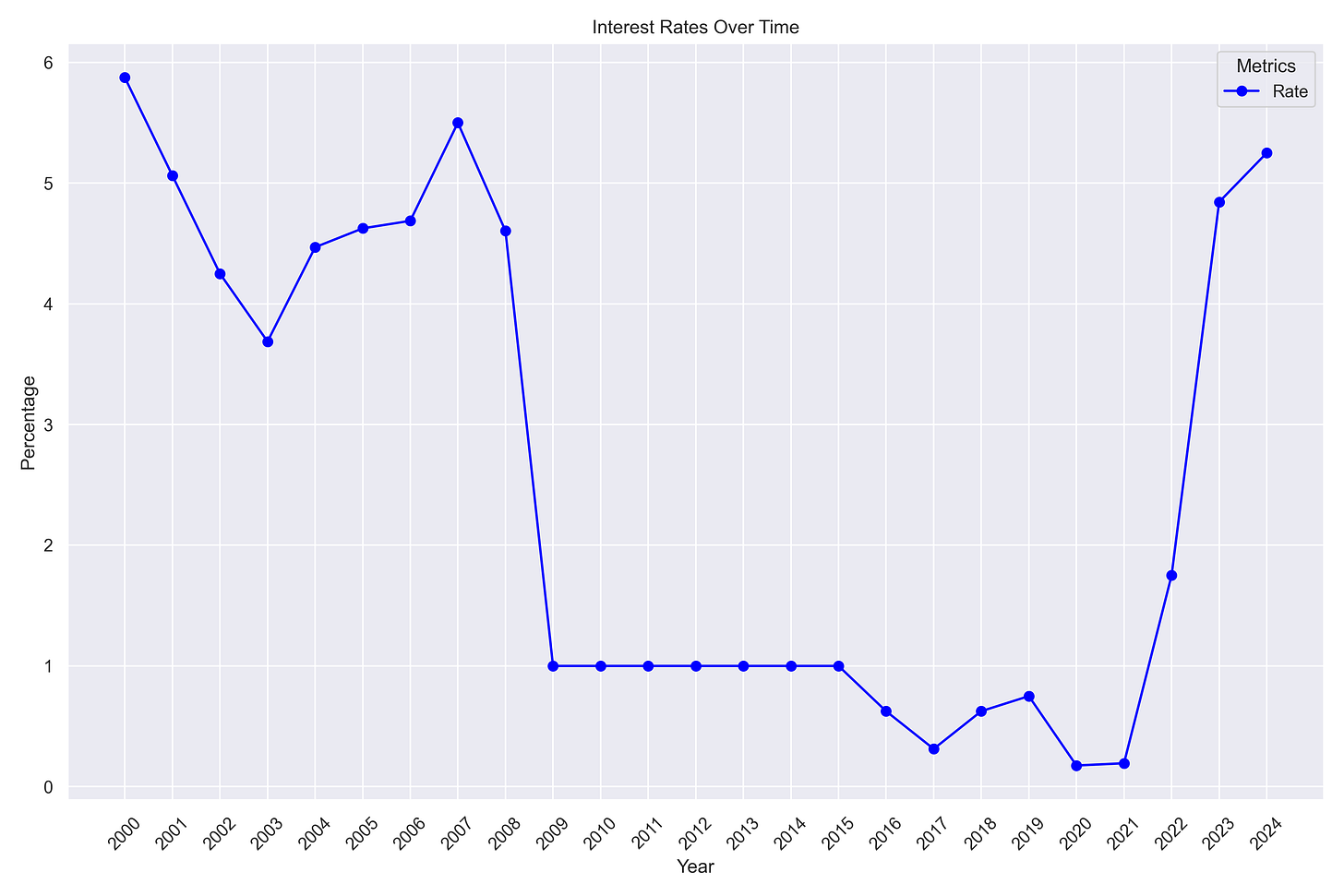

And here’s interest rates over the same time period

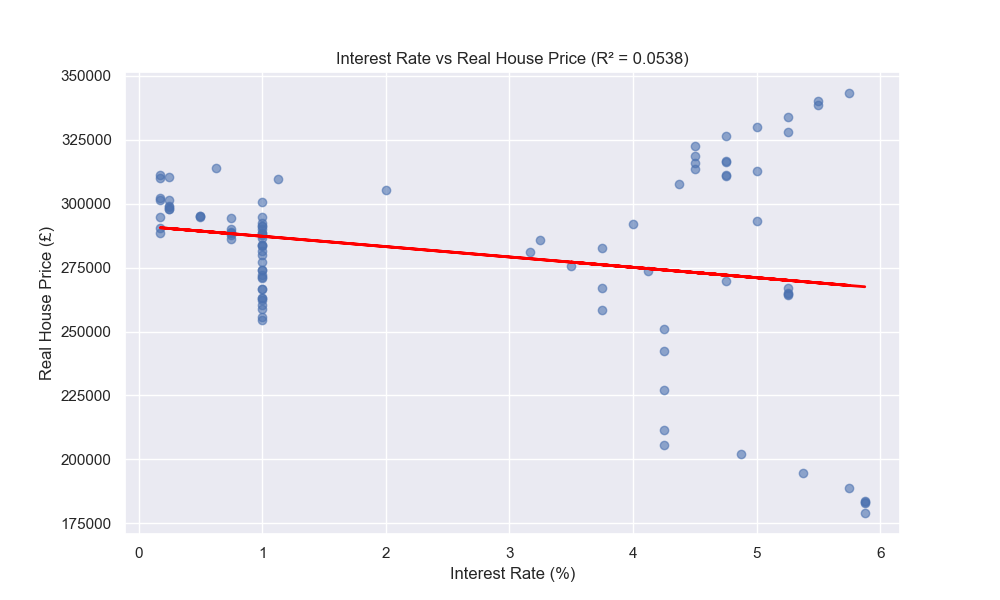

The obvious next step is to see if there’s any correlation between house prices and interest rates. I ran a simple linear regression over the data and this was the result.

The first is the regression model trying to find a correlation. The second is the residual plot. The Pearson correlation5 (the metric that determines the correlation)

is -0.23201410661561453, which means that there is a weak inverse relationship between house prices and interest rates.

In plain English, there is a relationship between them, but it’s *weak*. As in, there’s some correlation but not much.

This might seem surprising but apparently it’s not. Many factors affect house prices and while interest rates probably have an effect, they aren’t the only major factor.

What does this mean then? Well, it means that we can’t use past house prices and interest rates as an indicator of where the market is going to go. For us, and our model, this means that the historical data is effectively worthless. Based on the data I’ve analysed I can’t look you in the eye and say that a rise in interest rates will reduce house prices. Looking into this is a project for another day.

What we’ve learnt

The main purpose of this assessment was to “run the numbers” for buying vs renting. Having done so, it seems that 80% of the time buying is better over a five year timeline.

Obviously there are a lot of assumptions made in this model. The point was not to find the perfect way to work out if buying is better than renting on a timeframe, but to explore ways to actually run the numbers. Hopefully this pose will give you some ideas of how to do it.

I should also add that this is just one way for crunching the numbers, and it’s by no means a perfect one. I haven’t done anything to truly work out what makes house prices go up or down, nor have I done anything to properly predict interest rate rises, and I haven’t included anything that would simulate market conditions, but we’ll do that next time.

For a lot of people (myself included) buying a house is a deeply emotional thing. It’s the culmination of years of hard work and represents a significant milestone. No amount of mathematical magic can take away from the fact that it’s your home and you can do what you wish with it.

Which brings me to my final point, which is my main takeaway, which is that it takes a long time to (17 years in my estimation) to make a house profitable. Unless you get a good deal and somehow knock off 100k of the value of a property, you need to be in for the long haul.

https://curvo.eu/backtest/en/market-index/sp-500

https://www.checkatrade.com/blog/cost-guides/house-maintenance-cost

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monte_Carlo_method

https://www.thisismoney.co.uk/money/mortgageshome/article-14072297/Three-major-banks-hike-fixed-rate-mortgages-costs-RISING-Bank-England-cut.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pearson_correlation_coefficient

this was such a fascinating read!